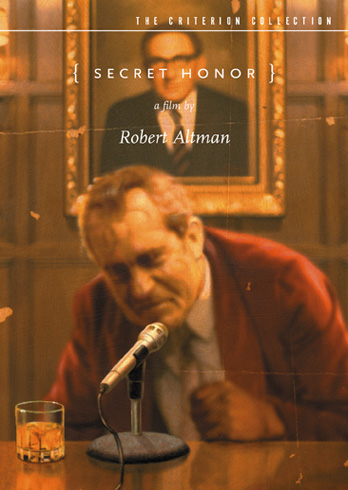

Secret Honor

Robert Altman, 1984, USA [Criterion, 2004]

Frankly, I didn’t think that a stage play – and a one-actor play at that – could make an adequate transition to the screen. Typically, the intimate conversational setting that is afforded by live theatre is more conducive to the conventions of the “one-actor play” than the temporal and material distancing of subjectivity that is cinema. And yet, since I consider him to be among the forefront of North American directors of the past few decades, there was no real reason for me to question Altman’s abilities. Three Women and MASH are among my most favourite films, and while Secret Honor does not have quite the impressive scope of either of those films, it serves to elaborate an analysis of modern culture which I feel is very prescient.

At the point of Nixon’s life in which the movie opens, Milhouse has sequestered himself in his house with some gin, a handgun, and some technology to aid in his seclusion. A neo-White House is constructed, with ex-Presidents lining the walls of his office, as well as an apparent secretarial staff as signified (and perhaps solely so) by the technologies with which Nixon has surrounded himself. Philip Baker Hall (the library nazi from Seinfeld, for you pop-co kiddies) gives a brilliantly prolific non-stop monologue of legal defence, confession, historical analysis, and nostalgic reverie. What emerges from this clearly delusional man who seems to have come to the extent of his sanity is a sense of pathos and subtle vulnerability that tears down Nixon’s mystique as Republican Nazi and humanizes him considerably.

This is, however, not my favourite depiction of the man, as there is indeed something sublime about Futurama’s Macross-Plus Nixon.

In narrative terms, the film/play concerns the absolution of this most-hated of ex-Presidents. While his actual rants are clearly the product of a mind pushed to delusion, Nixon quite rightly interrogates the complicity of the American population and the entire political system that is American democracy. Most important in this regard is the typically absurd strategies which emerged from the paranoia of the Cold War. American politics sought to control the population against the invasive tyrannies of communism through guidance, forced or otherwise (the country is after all a republic, and not a true democracy in the technical sense). Nixon felt that he was a scapegoat to this process: an axe-man who was himself martyred. America wanted a suicide for its most important martyr, and Nixon himself was determined not o follow this script.

I myself am more interested in Altman’s portray of Nixon as a prisoner of technology, forced to relate to other people only through a technological medium, which in this case is the magnetic tape which recorded his monologues. His compulsions seem to betray him as an Idoru construction: a psychology of non-existence except as re-presented back by a technological form. Would Nixon have killed himself if he had been denied access to the technology to record his thoughts? This sense of absolution through the transmission of identity to a future generation is a concept Derrida once described as the jouissance of archival inscription, a particular mark which he analogized to circumscription – itself a technology of inscription, medical technology, a means for ensuring continued (non-infected) reproductive health and ultimately the monitoring of such within the public sphere. Quite rightly, Altman focusses quite a bit on this technological archive, with several important sequences which highlight the security cameras which Nixon has aimed away from the outside world and onto himself. These monitors are precisely the “Jury” to which Nixon himself appeals for forgiveness throughout the film. I cannot in this context ignore the practical issue of Altman recording the play in this context. I don’t wish to elaborate too broadly here, yet Altman seems to be indicting himself as a passive observer of not only political action in this instance, but of subjectivity itself; the camera as critique of psychological drives, and more importantly as a compulsion made particular by individuals (filmmaker, viewer, etc).

Altman’s films typically delve into hybrid subjectivities, and yet there remains a dislocation in Secret Honor that I myself find very appealing for biographical art products. Too many bio-pics try to immerse the viewer into a sympathetic collusion with the supposed psychological motives of the subject in question. Altman chose to passionately indict our voyeurism as one and the same as Nixon’s desire to rationally control the irrational, a strategy that was to have dire political consequences for the 20th century.

Note: since Criterion DVDs are ridiculously expensive in Canada (this one lists for around $60) thanks to a distributor who adds too much of a markup, I got my copy of Secret Honor from the Hamilton Public Library. Whoever is purchasing DVDs for the HPL, my hat is off.

No comments:

Post a Comment