Upon encountering the aural landscape of Michael Waterman's Robochorus installation, one cannot help but consider the ontology of human creativity. Must all aesthetic experiences spring directly from the artist to be regarded and savoured as a means to discern the contents of their soul? More precisely, can the expressions of an artist be authentic when voiced by a third party? If one is to have faith in transubstantiation by means of pencil, musical instrument, or paint brush, surely there is space in the religious cannon to include machines, robots, and electronic devices.

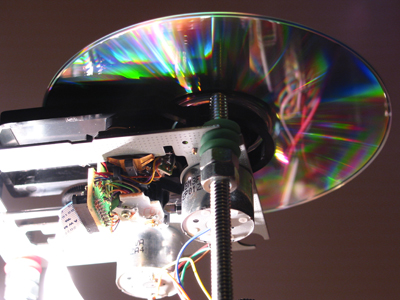

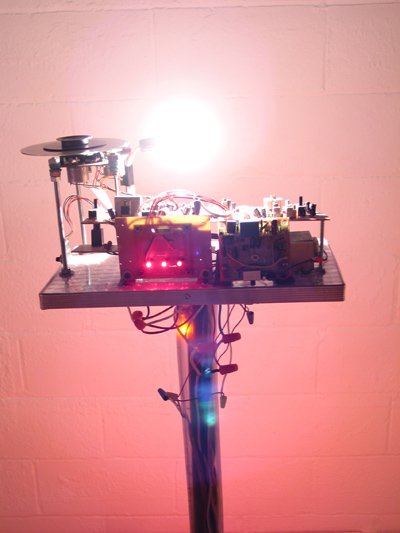

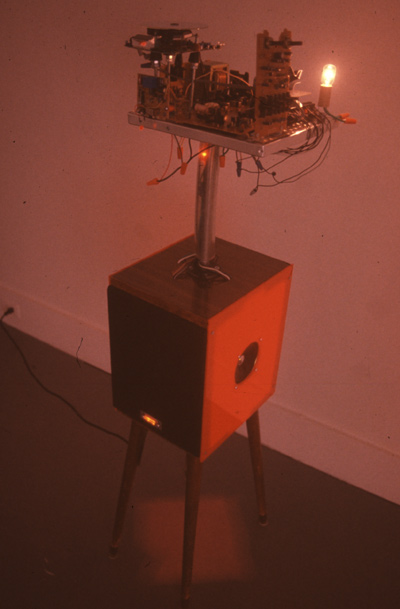

Waterman's history as a purveyor of bricolage and recontextualization greatly informs his latest installation. The eight individual Robochorus "singers" are homebrew anthropomorphic robots manufactured from the consumer audio detritus of several decades. These sentinels are located throughout the gallery space and sit mute without viewer interaction. When their internal motion sensors are triggered, the figures self-illuminate and begin to emit one of eight harmonic pitches in response to external stimuli. It is with these sounds that Waterman's interest in collage is most evident. Each of the eight tones is comprised of numerous audio sources, including radio broadcasts and environmental audio, which combine into a single, polyvalent drone. As the eight robots are voiced in the harmonic series, when all of them are triggered they can be heard to sing in conversation with each other. Taken together, the robots form the latest in retro home entertainment made public.

Part of Waterman's intention is to demonstrate the influence of commerce on our appreciation of art. The artist seems to want to bring the latent ambiguities of modern electronics and consumption to the fore. By triggering the robots and making them come to life, the audience gains a degree of control over the electronics that Waterman has put into play. Normally, we walk through the valley of technology with blinders; the vast majority of the population has little or no operational understanding of the devices that are consumed. This lack of understanding when merged with late capitalism's mantra of planned obsolescence has resulted in our present-day throw-away economy, which interpellates us as contingent psychotics disregarding the apocalyptic damage we are doing to our biosphere while simultaneously feeding off our nostalgic instincts for the purity of our collective past. We live and breathe garbage on a habitual basis. With Robochorus, Waterman has restructured our forgotten machines from their original functions to a more primitive and abstract level to allow a greater degree of understanding and sympathy.

What was once the latest in high-fidelity audio equipment has here become recontextualized into the latest in post-human technologies. Our machines play on, long after they have become obsolete and forgotten (by extension - does art outlive our critical interest?). By situating the listener as principle agent within a continually changing aural geography, Waterman's robomorphic singers demonstrate the very human characteristic of wanting to be loved (or more precisely, wondering why their love is no longer being returned when once it was so freely given). Individually, their voices are polyphonic yet highly articulated. When heard en masse, the effect is of an unarticulated yet aurally rich cluster of voices, situating the listener as chief conductor.

Several critical responses quickly elicit themselves. Am I supposed to understand what these robots are telling me? Do they themselves understand, or are their utterances the robot equivalent of a nervous tick? While the installation might suggest movement and progression akin to a narrative, when examined in more detail the piece becomes much more abstract and schizophrenic as the individual sound sources become supra-liminal. In some circles this aesthetic is named microsound: audio, when listened to under the microscope as it were, reveals increasing amounts of information. It is the impossibility to properly locate sounds that gives Robochorus its semantic resilience. Robochorus wishes to engage at both the macroscopic and the microscopic level, and yet this very process of "straining to hear" brings the listener back full-circle, (sitting "alone") in a darkened room, illuminated by the robotic extensions of humanity. The point, dear listener, is yourself, listening.

Michael Waterman's Robochorus runs from May 5 until July 9 at the Hamilton Artists Inc.