It's not that often that I choose to review older material, but this time I feel the need to promote the work of an artist pro bono. Thanks to my typical mid-winter hibernation, there has been a lot more time lately for the anti-social things that I love, one of which being graphic novels. I've been continually putting off an attempt to read the entire Cerebus series in one go thanks to certain, er, "responsibilities" that have come my way recently. Then comes a wee little snow day, and already I've gorged myself on several books.

This is what I would consider the best of the bunch -- mainly as the others included Spiderman and Batman ephemera. Montreal artist Julie Doucet has gained a good deal of publicity for her books, which combine domestic scenes with a particular sense of poetic realism in terms of narration and visual design. She rarely appeals to what I like to call "grand design" narrative, which, broadly speaking, is a means of attempting to melodramatize a story beyond itself. By this, I mean to suggest stories which appeal to their ontology in a rather banal and obvious way. Think of a story in which all of the actions and events which occur conveniently underline the themes or characterizations of the story without any other sense of logic behind their existence. This appeal is one of the author to him- or herself, and the last thing that I want masturbatory writing to attempt is structural realism. It does not aid a reader's uptake (at least not this reader), but rather grand design narratives serve to show themselves as stories which could be nothing but what the author has presented, a hermeneutic seal of self-legitimization. We've all seen and/or read bad deus ex machina stories. I am of the opinion that such is a failed aesthetic, and one which frequently lets authors off the hook without them doing too much work to understand the world around them.

Moving on...

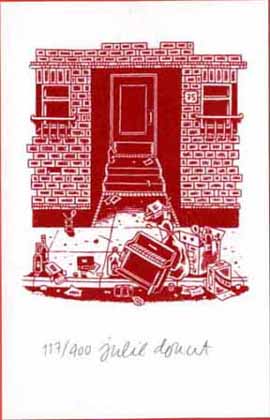

My New York Diary is a brief autobiography of the author during a time in her mid-twenties when, seeking a career in cartooning, she moves from Montreal to New York. Now I'm sure that the artist-trying-to-make-it-in-New-York is perhaps the biggest cliché in modern culture. And yes, the art does indeed owe a hell of a lot to Art Spiegelman. Doucet has a great ear for dialogue however, or more specifically for what remains almost-spoken in relationships. Some of this comes across through her inner thoughts. For the most part however, she leaves the important aspects of characterization to small graphic details such as the manner in which her cat responds to her New York boyfriend in the background of several panels.

It is precisely these little details that bring joy with every page. Doucet's bobbly-headed figures are irrepressibly endearing, especially when they get high and start cursing at each other in the nude. Perhaps it is the fighting which I find most appealing. Maybe it’s the sheer helplessness and uselessness of Doucet’s male characters, who seem entirely burdened by the weight of their bad decisions and yet do not seem to be conscious of this fact. Or perhaps it’s Doucet’s somewhat casual attitudes toward the valuation of meaning and the attribution of significance which stands out the most for me. Her characters are entirely believable as they exist almost entirely within prisons of their own derivation. They act akin to Foucault's interned within the panopticon: ever guilty, they either self-police or are eternally condemned. Doucet herself realizes this fact by the end of the novel, during a period of a few weeks when she comes to the realization that life for her cannot continue with her New York boyfriend in the picture. This breakup is not sentimental, but rather entirely realistic in the sense that both actors are engaging in a mutual process of misfiring, with each mistake reinforcing the mistaken emotions of the other person. It is a tragedy that thankfully is played entirely without melodrama (a taste if which we were given at the beginning of the novel during a boyfriend's feeble attempt at suicide).

With events such as these, Doucet seems to be advocating a certain laissez-faire approach to empirial significance. Sure, things such as breakups and such are milemarkers in our respective lives. But if all we suffer is the other person, or the lack thereof, then should we not be examining people and not events for meaning? Events are given significance by relations created through nostalgic reverie. With the simple, random, and even casual manner in which even the most meaningful relationships in our lives come and go, we are kidding ourselves with all of the melodrama of significance. Doucet serves us the reminder that such things are daily banalities, meaning little except to ourselves. Meaning comes at precisely the moment when the story of such things gets told and retold. Then again, such is the purpose of diaries: simultaneously private and public, singular yet universal, they are the material form of the nostalgic gesture, the means by which we attribute meaning to those little banal narratives that we call ourselves. This wake, this breathing of life into otherwise ancient memories, is the true sense of self that we can give to other people when they lack our immediate presence. It is for this reason that Doucet ends her book simply and abruptly with a three-page winter exodus of the city that involves her, her apartment, and her cat. Oh, and the not-so-subtle irony of an amateur marching band. Story over. She's come and gone. And we never really were in Julie's presence anyway!

Some of us like to engage ourselves with art that reinforces and legitimates our sense of self. When we find characters and stories that are as dysfunctional as we, a certain sense of homecoming washes over us. I now feel less isolated from society by the various manners in which I miseducate myself and those around me. Thanks to the ever-increasing circulation of Montreal’s Drawn & Quarterly imprint, you shouldn’t have too much trouble finding yourself a copy for the next snow day.

No comments:

Post a Comment